re{volt}ing

re{volt}ing, is created in response to John Gabriel Stedman’s Narrative of a Five Years Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam. Offering visions both historical and speculative, the works in this show span time, space, and media to manifest symbols of embodied agency in the context of global slavery.

Flee Plantation, linocut print with oil based ink on Stonehenge paper, 50”x 26”

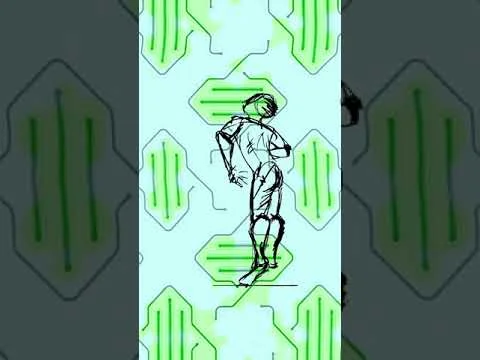

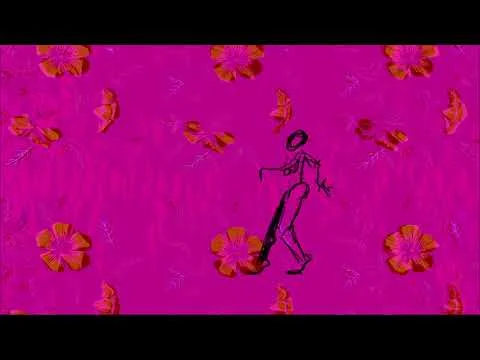

Joanna Twerk left, hand drawn animated loop, chalk on construction paper.

Neptune spared a coup de grâce, linocut print w/ oil based ink on BFK rives paper, 48"x 24”

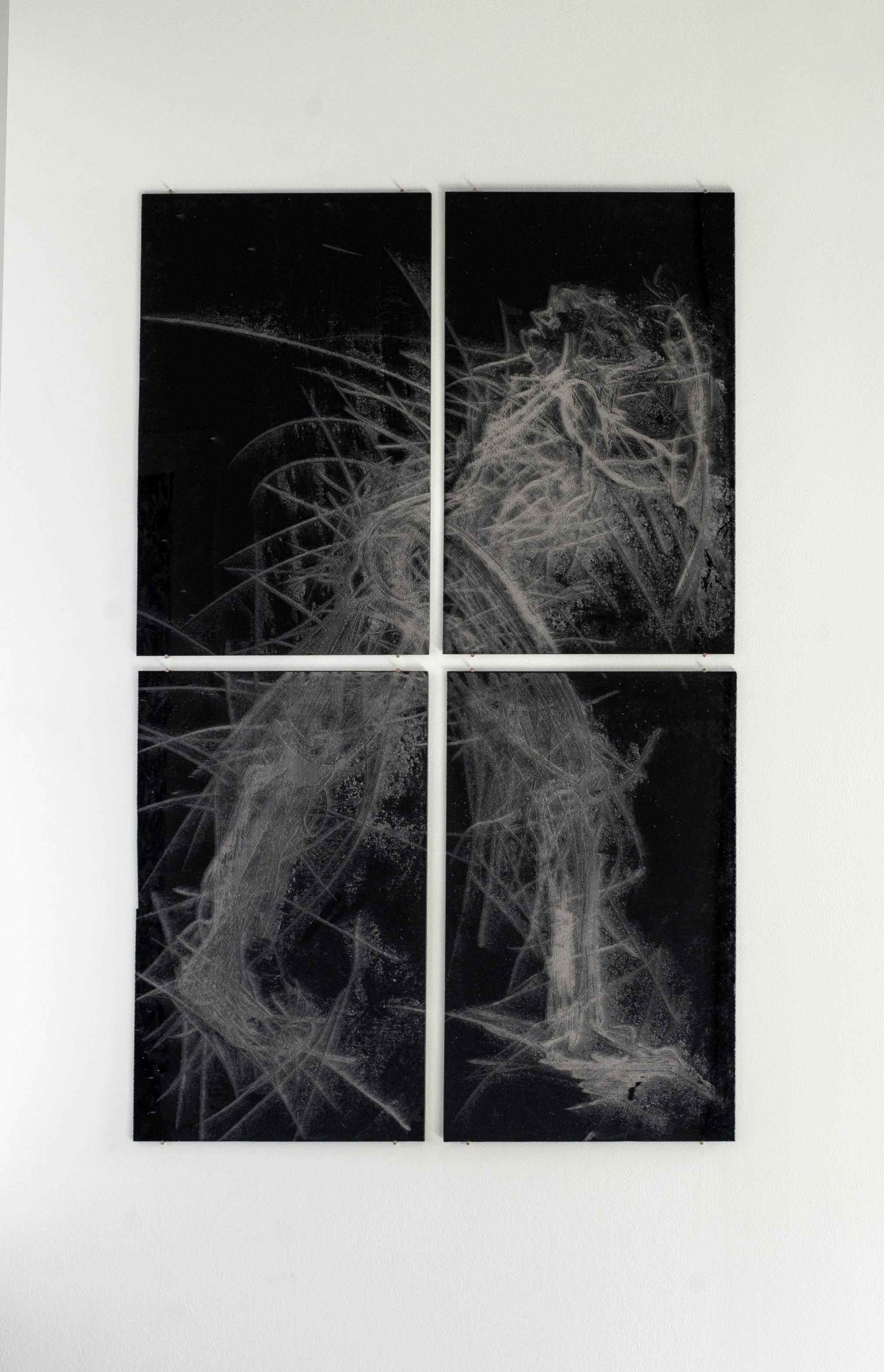

a Firm NO! Fuck your loathsome embraces, laser cut engraving in plexiglass, bronze nails, acrylic dust, 31”x19”

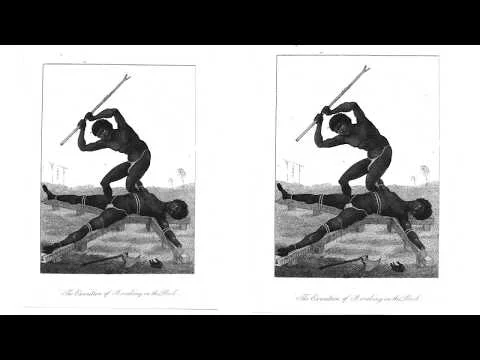

In his bestselling 1796 narrative, accompanied by engravings by William Blake, Stedman recounts his experience as a British-Dutch colonial soldier in the then Dutch colony of Suriname. In addition to romantic descriptions of the landscape and the social mores of Suriname’s indigenous, enslaved, and settler colonial residents, his written observations center on the horrors of slavery, depicting scenes of torture in great detail, with seeming empathy for the plight of individual slaves. Together, Stedman and Blake portray black resilience while obscuring white violence, their visions suggesting the grace and strength of victimized black bodies, the tragedy of torture. Stedman’s stance on abolition, however, is less clear.

It is this ambiguity that Lee-Johnson explores in her linocuts, animations, and installations. Working under the aliases of twin selves: Academia Graphít and Discourse Jockey—one a revisionist, the other a futurist seer—Lee-Johnson surfaces invisible worlds of joy and resistance. In her worlds, the agency of the enslaved figures, and of black bodies writ large, is always fraught—a striving within sites of extreme violence and oppression. Following D. Scott Miller’s theory of Afrosurrealism, Lee-Johnson suggests that liberation under oppressive circumstances—within a white supremacist patriarchal system—is never quite free, but that the invisible might be mined and scored to produce subversive sights.

The exhibition’s title, re{volt}ing, signals not only a visceral reaction to the disgusting violence perpetrated under racial slavery, but also the insurgent potential of revolution, the energy of the volt. In Torture Triptych, Lee-Johnson responds directly to Stedman’s detailed and exalted depictions of violence, re-envisioning three particularly brutal episodes of punishment and proposing new ways of looking—exaggerated hands and feet signifying the vitality of a body in control, onlookers simultaneously implicated and implicating the viewer. Both Flee Plantation and Joanna (twerk left) tease out the valences of power and spectacles of liberation: we don’t know where the maroons might go when they flee the burning plantation; we don’t know if Joanna (Stedman’s long-time sexual partner, an enslaved black woman), dancing at the gallows, is rejoicing her newfound independence or twerking for her life. These works challenge us to ask: is there capacity for freedom in individual actions? And can collective power emerge in the now?

In Marooning, Lee-Johnson offers dance—a generational inheritance and physical action—as a liberatory practice. Marooning acts as the control panel of a mothership, channeling Afrofuturist dreams of leaving Earth—or of already having left; but in this mothership, we have merely the veneer of control. Ancient warriors, presented as a diptych, act as ship captains, propelling forward through sea and space in a past-present-future. Sensuous animations take place in an unknown time and space, opening the alien, the magic in the past and present. With the spectacle of oppression gone, sound and movement take flight as embodied history, repeated ad infinitum.—text by: Reya Sehgal